Iron Meteorites For Sale

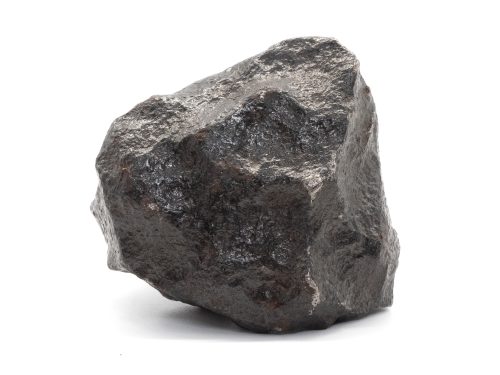

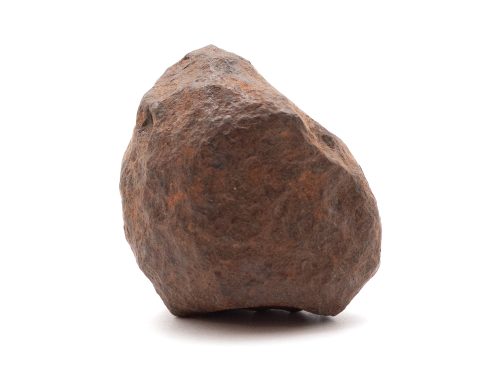

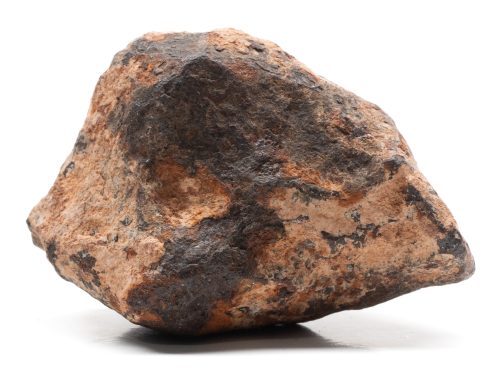

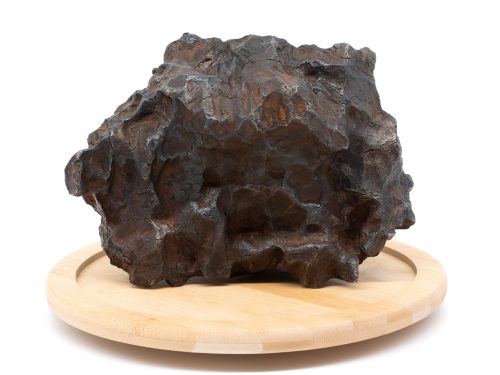

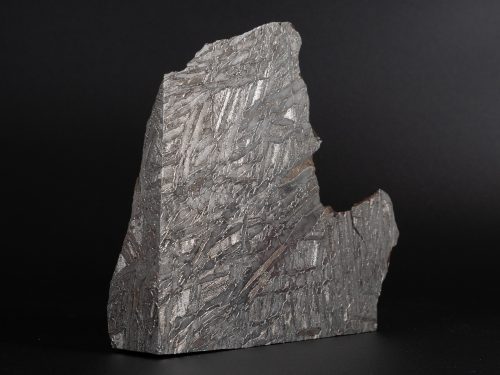

Medium sized Sikhote-Alin exhibiting thumbprints, and fantastic shape.

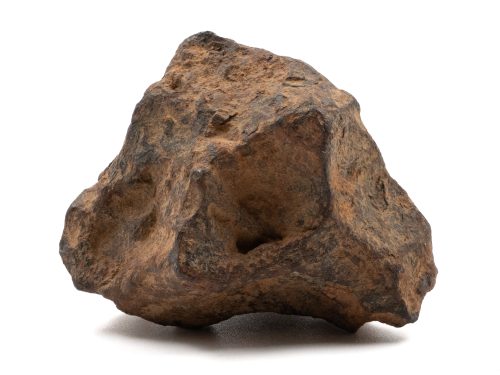

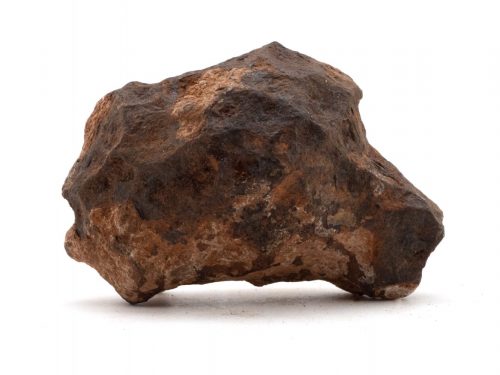

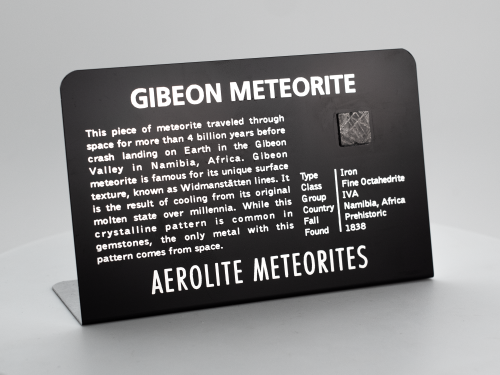

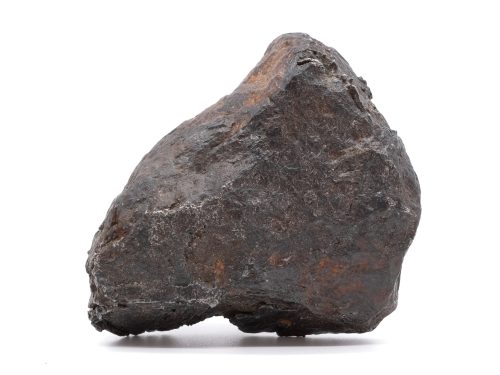

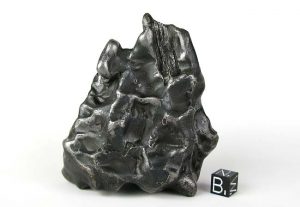

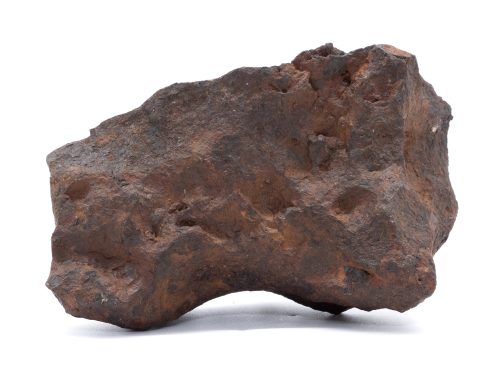

The most visually intriguing of meteorites are also the heaviest and the most recognizable. They come to us from large asteroids with molten cores that once orbited the sun between Mars and Jupiter. Extremely slow cooling of those cores, over millions of years, allowed nickel-iron alloys to crystallize into fantastic geometric structures known as Widmanstätten Patterns. Much like snowflakes, the pattern of every iron meteorite is unique. Catastrophic collisions within the Asteroid Belt shattered some asteroids, sending pieces in all directions. Some of them eventually encountered Earth’s gravitational pull, resulting in a fiery journey through our atmosphere at speeds up to 100,000 miles per hour. Superheated to thousands of degrees Fahrenheit, the surfaces of these fragments melted to form beautiful sculptural indentations called regmaglypts or thumbprints — features that are unique to meteorites.

Our catalog of iron meteorites for sale is presented here, in alphabetical order. Click on any image for additional photographs. Specimens are fully guaranteed and we pride ourselves on outstanding customer service; contact us for additional information. We hope you enjoy this look at the remnants of the hearts of ancient asteroids.

Explore our wide collection of Iron Meteorites For Sale

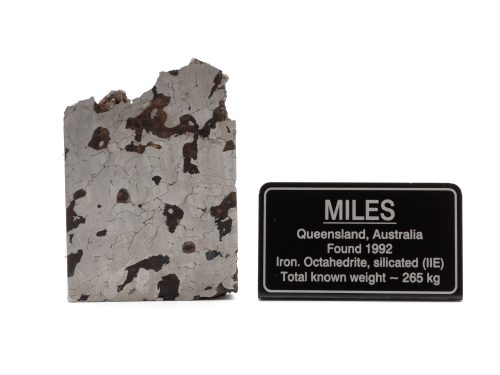

Agoudal Aletai Baja California Balambala Campo del Cielo Campo/Las Palmas Canyon Diablo Dronino Gebel Kamil Gibeon Henbury High Island Creek Miles Mundrabilla Muonionalusta Nantan Northwest Africa 11446 Northwest Africa 6565 Odessa Pierceville Saint-Aubin Seymchan Siderites Sikhote-Alin Soledade Taza The Eidson Iron / Arispe (Nova 057) Toluca Trenton Uruaçu Veevers Wabar Wolf Creek

Agoudal Individuals

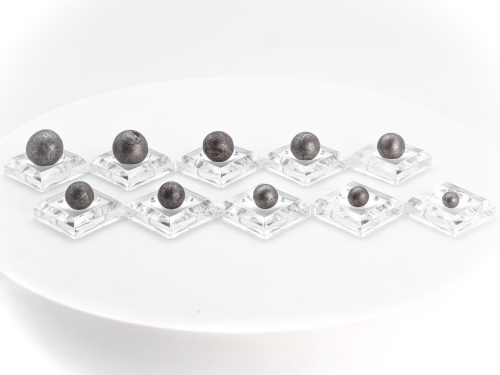

Aletai Crystals

-

Aletai 25.7g

$33.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 26.3g

$34.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 27.51g

$36.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 27.5g

$36.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 27.8g

$36.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 29.6g

$38.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 33.1g

$43.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 35.4g

$46.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 5.8g

$7.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 6.6g

$8.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 7.0g

$9.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 7.31g

$9.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 7.5g

$9.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 7.6g

$10.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 8.6g

$11.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 8.9g

$11.00 Add to cart -

Aletai 9.9g

$12.00 Add to cart

Campo del Cielo Individuals

-

Campo del Cielo 1,220.0g

$670.00 Add to cart -

Campo del Cielo 1,280.0g

$705.00 Add to cart -

Campo Del Cielo 1,321.0g

$725.00 Add to cart -

Campo del Cielo 10.4kg

$4,680.00 Add to cart -

Campo Del Cielo 17.8kg

$8,010.00 Add to cart -

Campo del Cielo 38kg

$32,295.00 Add to cart -

Campo Del Cielo 5.8kg

$2,610.00 Add to cart -

Campo del Cielo 6,254.0g

$2,815.00 Add to cart

Campo del Cielo Slices

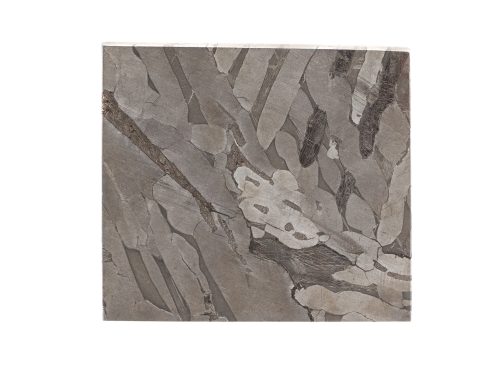

Campo Crystal

-

Campo Crystal 194.7g

$243.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 194.8g

$264.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 220.6g

$276.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 40.1g

$50.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 53.6g

$67.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 55.6g

$70.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 611.1g

$784.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 75.7g

$95.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 80.0g

$100.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 82.51g

$103.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 82.5g

$103.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 88.1g

$110.00 Add to cart -

Campo Crystal 92.4g

$140.00 Add to cart

Campo del Cielo Spheres

Canyon Diablo Individuals

-

Canyon Diablo 1,142.1g

$2,570.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 11.6g

$29.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 12.2g

$31.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 2,096.0g

$4,199.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 256.2g

$512.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 267.3g

$599.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 292.9g

$598.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 304.2g

$1,750.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 34.3g

$86.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 35.8g

$90.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 391.9g

$738.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 43.8g

$110.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 478.9g

$957.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 53.6g

$134.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 536.1g

$1,070.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 57.2g

$143.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 614.9g

$1,380.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 63.0g

$158.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 8.9g

$22.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 875.2g

$1,750.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 9.1g

$23.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 9.7g

$24.00 Add to cart

Canyon Diablo Slices

-

Canyon Diablo 16.9g

$68.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 23.0g

$92.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 30.2g

$121.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 33.4g

$134.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 35.2g

$99.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 35.9g

$143.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 37.7g

$150.00 Add to cart -

Canyon Diablo 88.3g

$353.00 Add to cart

Canyon Diablo Oxide

Dronino Slices

-

Dronino 10.6g

$32.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 107.8g

$323.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 13.6g

$39.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 137.0g

$410.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 157.2g

$472.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 18.2g

$55.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 203.5g

$610.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 22.5g

$68.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 24.7g

$74.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 25.2g

$76.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 26.6g

$80.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 31.3g

$94.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 38.6g

$135.00 Add to cart -

Dronino 8.2g

$25.00 Add to cart

Gebel Kamil Slices

Gibeon Sphere

Muonionalusta Slices

Odessa Individuals

Odessa Slices

-

Seymchan 15.3g

$46.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 16.3gr

$49.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 18.7g

$56.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 21.6g

$65.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 21.8g

$65.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 22.8g

$68.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 24.8g

$74.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 26.9g

$81.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 27.4g

$82.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 28.0g

$84.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 3,894.0g

$9,735.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 30.4g

$91.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 30.5g

$92.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 37.1g

$111.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 37.7g

$113.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 39.51g

$119.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 39.5g

$119.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 45.0g

$135.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 45.2g

$136.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 72.1g

$216.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 32.2g

$96.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 33.6g

$99.00 Add to cart

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel

-

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 107.9g

$188.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 140.9g

$211.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 193g

$337.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 46.2g

$69.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 66.8g

$100.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 69.5g

$105.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 73.4g

$128.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 87.7g

$135.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Shrapnel 91.5g

$137.00 Add to cart

Sikhote-Alin Oriented

Sikhote-Alin Individuals

-

Sikhote-Alin 37.6g

$451.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin 57.0g

$399.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin 59.6g

$417.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin 66.4g

$450.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin 84.8g

$593.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Geoff Notkin Collection 127.7g

$1,350.00 Add to cart -

Sikhote-Alin Individual 82.9g

$845.00 Add to cart