Stony-Iron Meteorites For Sale

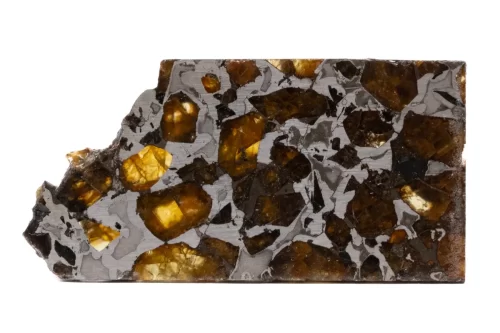

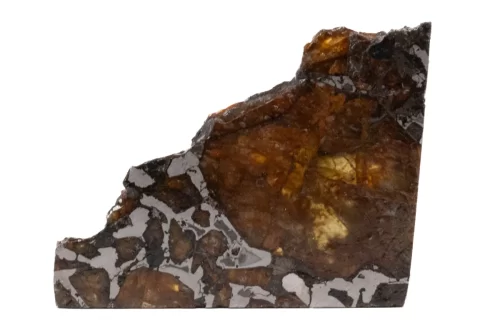

Fukang: The Reigning Queen of Pallasites

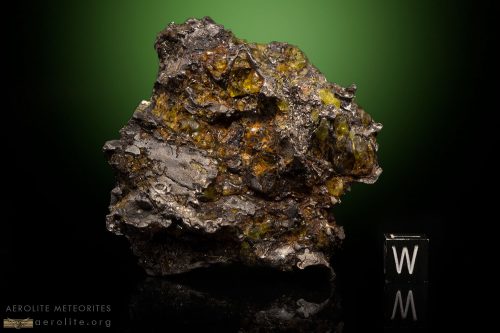

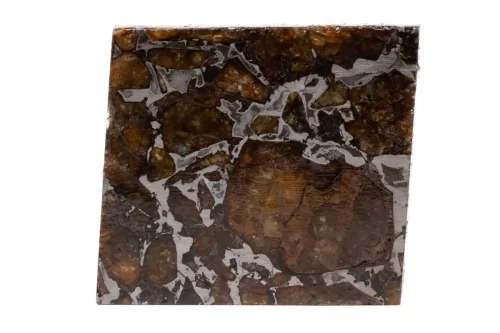

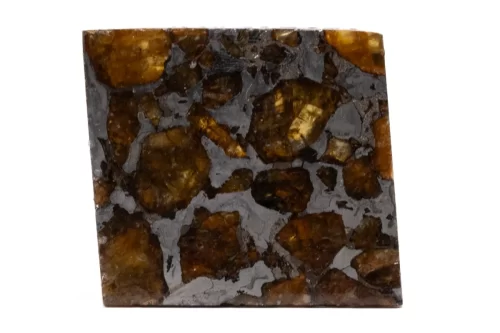

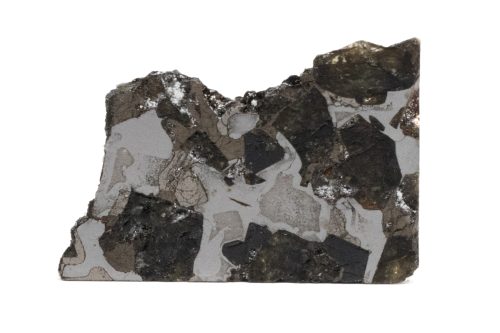

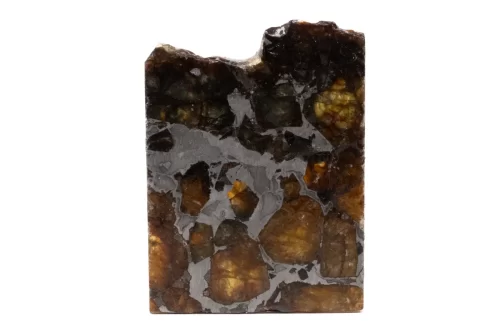

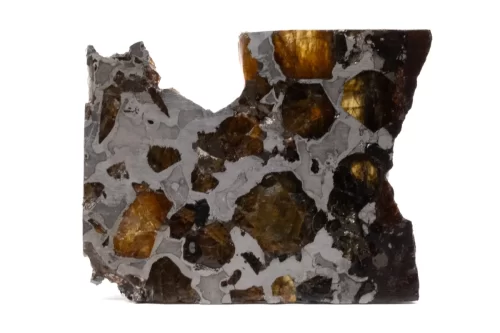

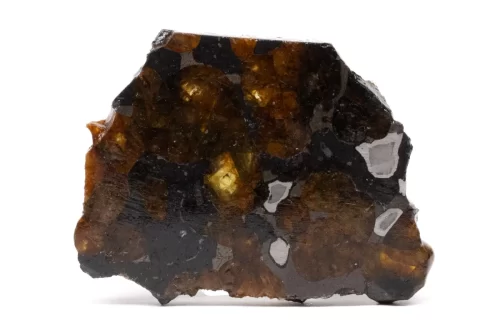

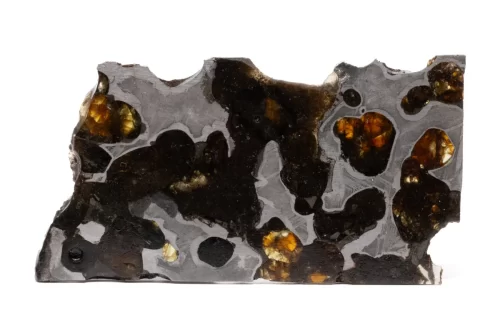

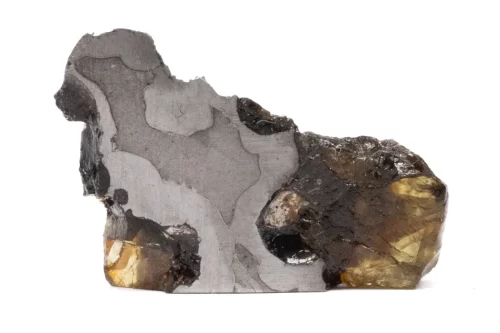

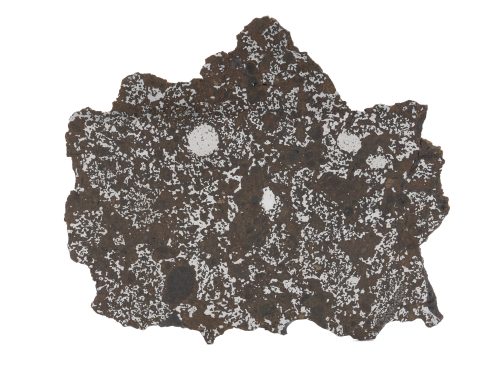

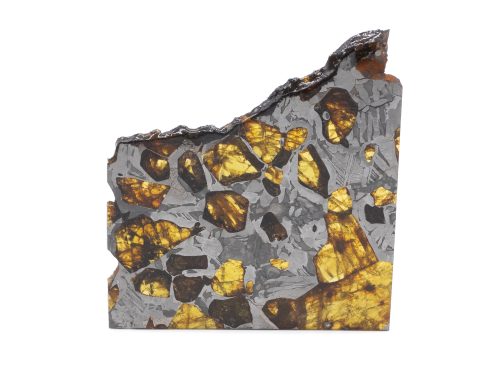

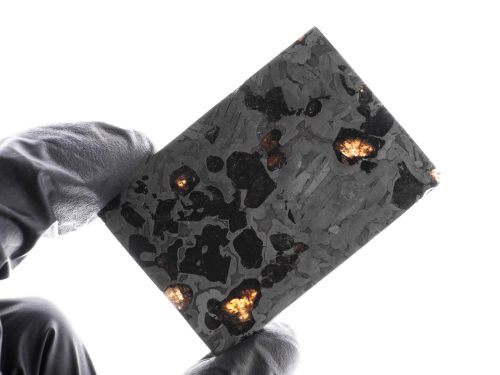

The rarest of the three main types of meteorites, the stony-irons are divided into two groups: the mesosiderites and pallasites. Mesosiderites are believed to have been formed by violent asteroidal collisions, millions of years ago in deep space.

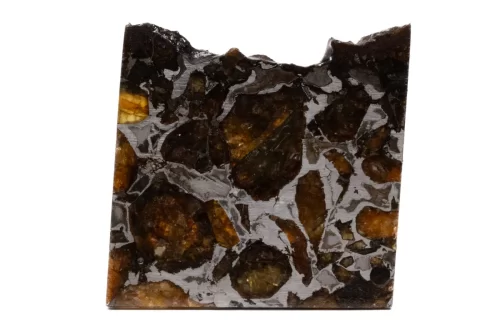

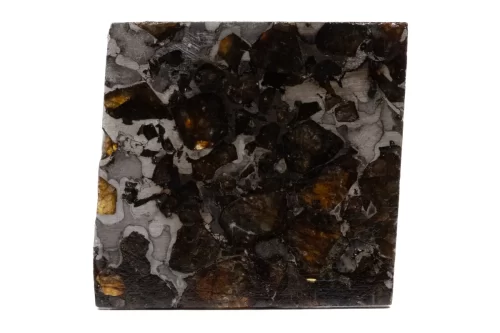

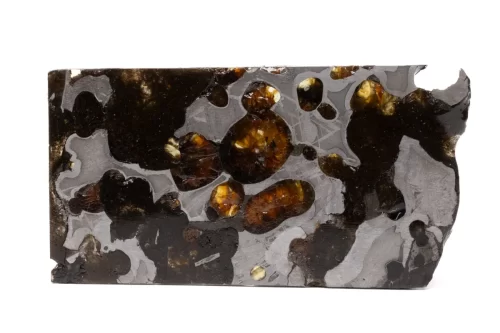

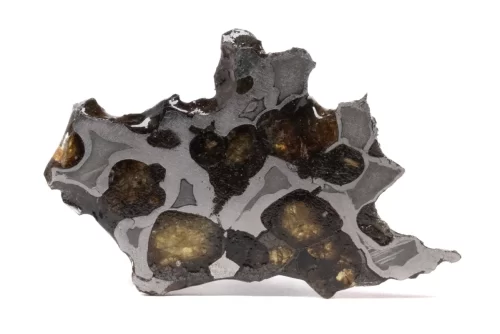

Pallasites are no doubt captivating—they’re unlike anything found on Earth, and their story is one of massive catastrophe. Tiny droplets of metal found have been found, in rare occasions, inside of an olivine crystals. These minute blebs have recorded ancient magnetic fields presents when their parent planetesimal was producing magnetism from its molten core. Such a phenomenon must have occurred at a very low temperature, giving scientists clues as to how pallasites formed. One explanation is that two planetesimals collided, injecting the molten metal found in the core of one into the olivine mantle of the other. The metal wrapped itself around crystals of olivine, forever encasing them as the metal cooled.

Pallasites are extremely rare. Out of the approximately 75,000 officially recognized meteorites, there are less than 200 known pallasites.

Our catalog of stony-iron meteorites for sale is presented here, in alphabetical order. Click on any image for additional photographs. All specimens are fully guaranteed and we pride ourselves on outstanding customer service.

Explore our wide collection of Stony-Iron Meteorites For Sale

Admire Bondoc Brahin Brenham Dalgaranga El Eglab 001 Fukang Glorieta Mountain Golden Pallasite Huckitta Imilac Northwest Africa 10023 Northwest Africa 7154 NWA 15428 (provisional) NWA 7657 Sericho Seymchan Pallasites Vaca MuertaAdmire Crystals

Admire Slices

Admire Nuggets

Bondoc Nodules

-

Brahin 14.8g

$175.00 Add to cart -

Brahin 15.5g

$155.00 Add to cart -

Brahin 19.5g

$195.00 Add to cart -

Brahin 21.7g

$217.00 Add to cart -

Brahin 22.4g

$224.00 Add to cart -

Brahin 22.5g

$225.00 Add to cart -

Brahin 36.2g

$434.00 Add to cart -

Brahin 37.3g

$447.00 Add to cart -

Brahin 68.8g

$963.00 Add to cart -

Brahin Pallasite End Cut 18kg

$57,750.00 Add to cart

-

Northwest Africa 10023 15.4g

$847.00 Add to cart -

Northwest Africa 10023 16.7g

$919.00 Add to cart -

Northwest Africa 10023 25.5g

$1,395.00 Add to cart -

Northwest Africa 10023 54.6g

$2,250.00 Add to cart -

NWA 10023 18.0g

$875.00 Add to cart -

NWA 10023 18.9g

$1,039.00 Add to cart -

NWA 10023 20.1g

$1,005.00 Add to cart -

NWA 10023 22.9g

$916.00 Add to cart -

NWA 10023 22.9g

$1,145.00 Add to cart

Sericho Slices

-

Seymchan 18.7g

$224.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 19.2g

$230.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 19.8g

$235.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 2,620.0g

$25,750.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 2,923.0g

$35,995.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 20.4g

$245.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 37.4g

$935.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 383.0g

$3,830.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 39.8g

$475.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 40.2g

$482.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 42.4g

$509.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 45.2g

$449.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 45.7g

$545.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 50.8g

$508.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 9,600.0g

$61,995.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan Cube 72.3g

$1,080.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan Sphere 34.9g

$975.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan Sphere 464.5g

$9,995.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan Sphere 5,084g

$105,995.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 34.7g

$415.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 44.0g

$528.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 45.6g

$499.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 60.3g

$720.00 Add to cart -

Seymchan 1,025.8g

$9,225.00 Add to cart