WHAT ARE TEKTITES?

The idea that continents on Earth today had once constituted a “supercontinent” was prevalent in geologic studies. Pangea was the supercontinent that existed in the late Paleozoic era and was centered on the Equator, surrounded by a vast “superocean” called Panthalassa. Scientists estimate that Pangea was assembled approximately 335 million years ago and began breaking apart about 175 million years ago.

Further studies posit that before Pangea, another supercontinent existed in the Neoproterozoic era, about 550 million years ago, called Gondwana. According to some theories, Gondwana and Euramerica (another continent), merged to form Pangea. The supercontinent was named by Austrian scientist Eduard Suess, who proposed its existence in 1861. Suess’s son, Franz Eduard Suess, walked a similar path to his father’s and would go on to study geology. The younger Suess would coin a term familiar to meteorite collectors and those studying the metaphysical properties of minerals: tektite.

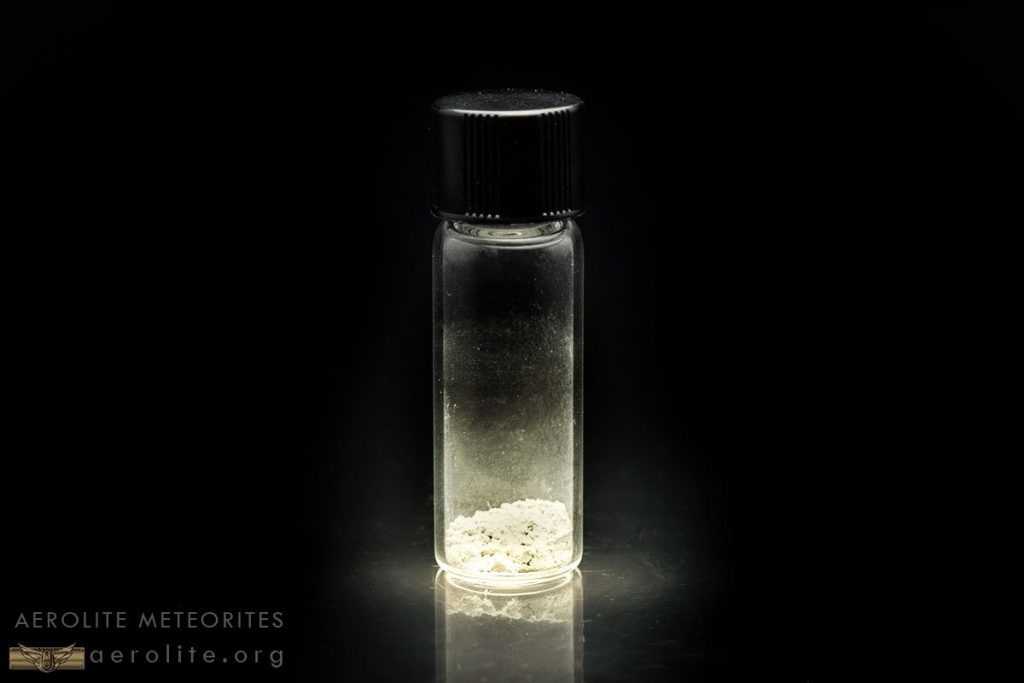

The word “tektite” comes from the Greek word for “molten.” Tektites come in a vast array of shapes and sizes. Moldavites, for example, are a gem-like green while Libyan Desert Glass pieces are honey-colored. Tektites form in a manner similar to terrestrial volcanic glasses, obsidians; they’re ejected during meteorite impacts. However, unlike volcanic glasses, tektites contain virtually no water, and their silica and isotope composition are quite different from obsidians. They also contain bands or particles of lechatelierite, a mineraloid that forms from quartz at very high temperatures. Lechatelierite is not found in obsidians and is common to tektites.

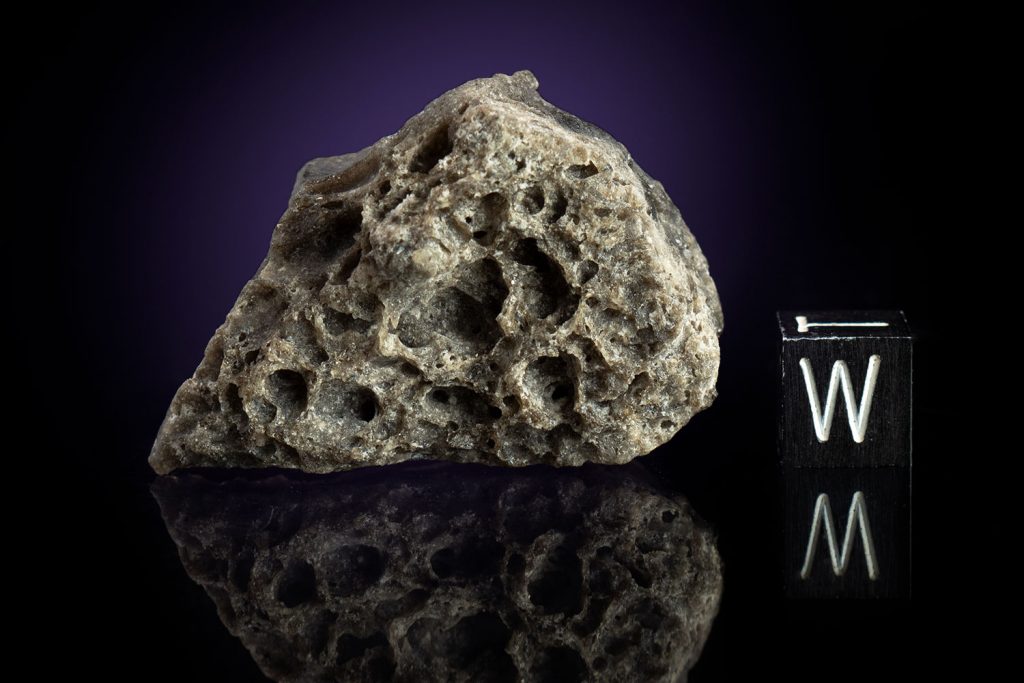

Tektites are traditionally divided into four groups: microtektites, which are less than 1 mm; splash-form tektites, considered the most “normal”; aerodynamically shaped tektites; and layered tektites. Splash-form tektites are shaped like spheres, teardrops, and other shapes you might expect something molten that solidified to take. Aerodynamically shaped tektites acquire their peculiar shape when they re-enter our atmosphere, like iron meteorites. Layered tektites are usually larger and have distinct blocky, chunky appearances and a “layered” structure.

The most widely accepted theory to explain the origin of tektites is that they came from terrestrial material that was ejected during a meteorite impact event. The debris either melted or vaporized, or both – the exact process they undergo is still poorly understood – and cooled as they fell back to Earth. This theory is supported by mineral inclusions of quartz, zircon, chromite, etc. in tektites and the fact that some tektites can be tied to an impact crater by their age and isotopic composition. However, some scientists debate this origin theory and believe tektites could have come from the Moon, an idea supported by Franz E. Suess.

Such explanations posit that tektites formed from volcanic activity on the Moon, which ejected the glasses into outer space, later landing on Earth. Scientists who support this theory cite tektites’ rare-earth and isotopic composition, physical properties, and other characteristics. There are numerous problems with the extraterrestrial origin theory of tektites, however, and most scientists agree that the characteristics displayed by tektites strongly suggest that they derived from terrestrial rocks. Even still, tektites are a major area of interest for those with an academic interest in meteorites, avid and amateur collectors, and even those interested in their metaphysical qualities.

Darwin Glass, Libyan Desert Glass, Moldavite, and Indochinites are some of the most alluring tektites, and we have several specimens available for purchase on our website. Shop here: aerolite.org/shop/our-impactites/

⋆ ⋆

⋆

⋆

FOLLOW US

RECENT BLOG POSTS

⋆

⋆